…more artistic musings

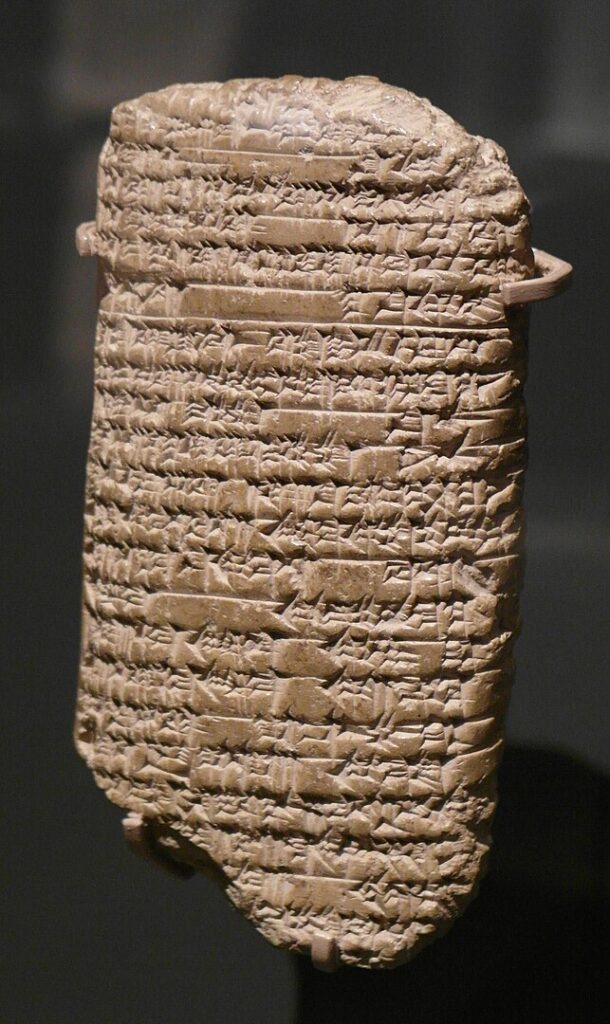

...Stated in the ancient Amarna Letter EA 11 the King of Babylon wrote to Akhenaten, the rebellious 18th Dynasty Pharaoh sent ten lumps of genuine lapis lazuli as your greeting-gift, and to the mistress of the house I sent twenty crickets of genuine lapis lazulia

The Ancient Amarna Letter EA 11 the King of Babylon wrote to Akhenaten, 1352-1336 B.C.

PAINT IT ANY COLOR AS LONG AS IT’S BLUE

For years the Home Fashion Industry has followed a prepared forecasted color palette. The successful Interior Designer has learnt to pay attention to every detail of the project no matter how minuscule. Today’s signature room requires much attention from the skilled creative. More is essential than simply hanging a painting upon a wall. And, for many that landscape or still life painting is at times used simply as an accent and is just one of many components that contributes luxurious opulence to a room.

But such was not the case during the RENAISSANCE. For, during this period in history status came from a specific pigment that was used. So special that even by today’s standards its status remains unchallenged. While it is known that the Italian Masters had a limited color palette there is one color that far outshone all others. This pigment was at least as important as the painting itself. Its name is ultramarine.

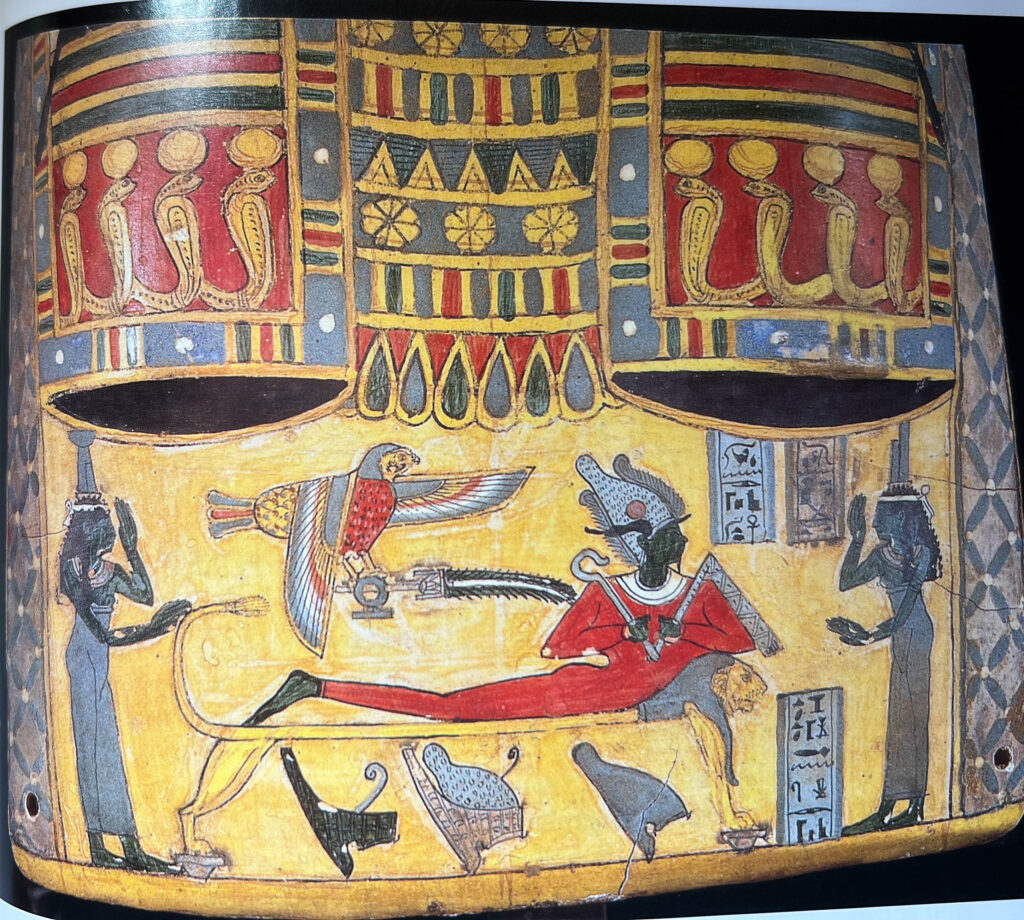

The semi-precious stone from Afghanistan, called Lapis-Lazuli was more precious than gold and obtaining it was extremely dangerous, just as it is today. It dates back seven thousand years when it was used in the royal tombs of Ur and Egyptian pharaohs.

Lapis is considered the rarest of stones, and mined mostly in Badakshan, Afghanistan, the oldest mine in the world. This same source for the Lapis-Lazuli supplied the pharaohs and the Renaissance artisans. Adding to this expense was the difficult and often long grinding process necessary to transform the ultramarine into granules. Even today while it remains rare it can be purchased only through selective distributors specializing in museum quality restoration materials.

Consequently, due to the high cost of this material, the early Renaissance artists reserved it for painting the garments of the Virgin Mary and the Holy Infant. This precious pigment made its first appearance in the early Renaissance painted altarpieces by Giotto.

KISS of JUDAS (1304-1306) by GIOTTO

Leonardo Da Vinci was required to sign a contract that specifically stipulated his use of ultramarine for “The Virgin of the Rocks” in London’s National Gallery.

VIRGIN of THE ROCKS by LEONARDO DaVINCI

Sponsors of Michelangelo and Raphael were also expected to pay an additional fee to the merchants who supplied the ultramarine. It then became the responsibility of these Masters to incorporate it into their commissioned compositions.

There remains an unfinished panel, titled “The Entombment,” dated 1501 by Michelangelo, also in the National Gallery. It remains unfinished because the twenty-four-year-old artist never received the shipment of the pigment from his patron.

The ENTOMBMENT (1501) by MICHELANGELO

By the mid-1500s, the Italian Master Titian extended the previously limited use of Ultramarine by using it lavishly when painting skies. However, by that time, Titian had a reputation for sparing no expense on his materials.

BACCHUS and ARIADNE (1520-1523) by Titian

Social and economical status in interior decoration has definitely evolved since the beginning of recorded history. While Renaissance Masters focused on status achieved through pigment choice, the Interior Designer of today is not as limited. However, for the artist and the consumer the color blue is here to stay as it was and remain always a primary color.

RECOMMENDED READING:

Techniques of the Great Masters of Art

COLOR: A Natural History of the Palette by Victoria Finlay

COLOR AND MEANING: Practice and Theory in Renaissance Painting by Marcia Hall

I WAS VEMEER

KREMER Pigment 2009 catalog

Nefertiti: Unlocking the Mystery Surrounding Egypt’s Most Famous and Beautiful Queen by Joyce Tyldesley

Quote from page 174 ” Amarna Letter EA 11 Moran, W I (1992), The Amarna Letters, Baltimore: 21-3

The Ancient Amarna Letter EA 11 photo: supplied by: rowanwindwhistler